It’s a bustling Saturday night at your local neighborhood restaurant. The dining room is only half full, but you know it’s a busy night because in-house delivery drivers — formerly bussers and dishwashers — are whisking dozens of orders in and out of the store, delivering family meals and wine flights to regulars. While barstools are mostly empty, patrons wait for their tables dutifully six feet apart, most wearing face masks. Someone coughs and customers shift nervously — several even get up and leave.

It’s a restaurant scene experts say is likely to become familiar over the next six months to a year as businesses reopen to modified operations and a consumer sentiment is marked by apprehension or fear.

“The restaurant industry will never go back to ‘normal’ again,” said Gary Stibel, an analyst at New England Consulting Group. “Memories are short; people will come back. But it will take a couple of years for traffic to get back [to the way it was before]. You’ll see a spike when we reopen the country — people are landlocked right now and want to get out — but that will soon level out.”

As America climbs out of the coronavirus crisis and businesses begin to reopen, albeit with radically different operational tactics, one big questions looms: Will the customer be back, and how quickly? And how will they be changed by the financial, social and health stresses they’ve endured?

The full evolution of the restaurant patron psyche is yet to unfold, but early clues already paint a picture of a cautious consumption. Researchers behind the Index of Consumer Sentiment from the University of Michigan predict that once the country reopens it will see a “short burst of spending” quickly followed by slower traffic as people will be cautious to go out in public particularly to crowded places like popular restaurants.

The full evolution of the restaurant patron psyche is yet to unfold, but early clues already paint a picture of a cautious consumption. Researchers behind the Index of Consumer Sentiment from the University of Michigan predict that once the country reopens it will see a “short burst of spending” quickly followed by slower traffic as people will be cautious to go out in public particularly to crowded places like popular restaurants.

“It will take some time for the majority of consumers to again become comfortable enough to resume their normal spending patterns,” the researchers said in their April Consumer Sentiment Index report.

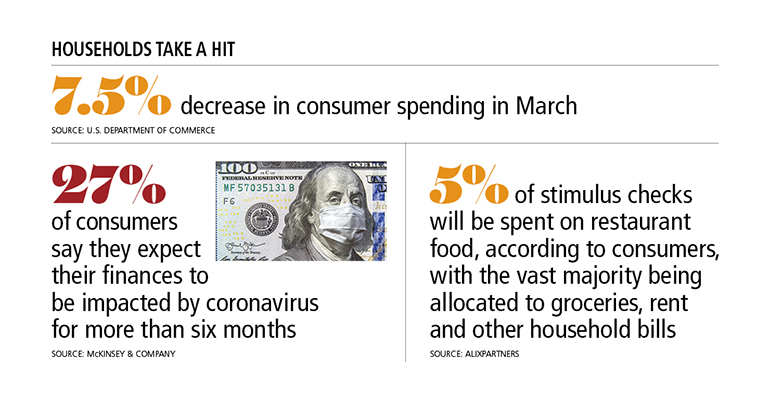

Besides fear, the other major consumer inhibitor is economic distress. According to the latest data from the U.S. Department of Labor, 3.8 million people filed for unemployment the week of April 25, pushing the unemployment numbers past 30 million over the past six weeks, or 20.6%, a number that has surpassed the economic recession of 2008.

There are signs those stresses are already driving more cautious behavior. Personal spending was down 7.5% in March, according to the Commerce Department. The Consumer Confidence Index fell nearly 27% from March to April as the crisis wore on, according to the Conference Board.

Fear as a major driver

Experts say fears around health, safety, and an economic recession will shape the restaurant industry for months and years to come. Even as state governments begin to give the go-ahead to reopen businesses and public spaces, people will likely be hesitant to dive back into their old lives.

Restaurant operators would be wise to take that into account, Stibel said. Any marketing research that restaurant companies might have gathered on what their customers want has to be “thrown out the window,” he said.

Restaurant operators would be wise to take that into account, Stibel said. Any marketing research that restaurant companies might have gathered on what their customers want has to be “thrown out the window,” he said.

“From now on, you’ll have to be segmenting based on fear instead of demographics,” Stibel said. “Some people are scared because of their age, others because they have young children. When this is all over, there is a segment of the population that will jump for joy and get in their car and spend, but that will be a small section of the population.”

Many consumers will respond to visual signals that show customers health and safety are a priority. Extra sanitation protocols, contactless delivery options, masked and gloved employees and clear social distancing guidelines can all ease a nervous consumers mind.

Many consumers will respond to visual signals that show customers health and safety are a priority. Extra sanitation protocols, contactless delivery options, masked and gloved employees and clear social distancing guidelines can all ease a nervous consumers mind.

Convenience reigns

Although delivery was already top of mind for the restaurant industry before COVID-19 hit, once dining rooms closed in March, it was sink-or-swim for restaurants that had not focused on off-premise before. But even as the effects of coronavirus begin to let up in the coming months, the push for convenience-focused service is likely to get stronger.

“Companies with strong digital properties — those with apps and rewards programs — are in demand more by consumers right now,” analyst Andy Barish, managing director at Jefferies said. “Demand shifting to off-premise would also necessitate smaller restaurants, less dine-in space, things the industry had already started thinking about with delivery becoming a larger factor.”

While restaurant dining rooms remained closed across much of the country, restaurants had to rely on third-party delivery apps, their own in-house apps, and social media to communicate with customers. The key takeaways from this entirely off-premise-focused, challenging period of the restaurant industry are easy digital access and personalized communication: If you had already heavily invested in digital delivery tools, you were one step ahead of the curve.

While restaurant dining rooms remained closed across much of the country, restaurants had to rely on third-party delivery apps, their own in-house apps, and social media to communicate with customers. The key takeaways from this entirely off-premise-focused, challenging period of the restaurant industry are easy digital access and personalized communication: If you had already heavily invested in digital delivery tools, you were one step ahead of the curve.

Growing demand for delivery might also loosen the hold third-party companies have on the delivery segment, as restaurants decide the revenue stream is worth additional in-house investment.

“Many restaurants have been forced in the past few weeks to do direct delivery and have found it’s doable,” Stibel said. “Figure out a way to insure your employee that has a car and make them a delivery person. Once they realize this is doable, the savings will be huge.”

Old rules no longer apply

The COVID-19 crisis has nudged restaurant brands to get creative with their menu and marketing offerings. From chains like Subway and Panera Bread launching grocery delivery and pickup, to family-friendly restaurants offering unique meal deals like fast-casual chain Fresh Brothers’ Jumanji movie bundle with pizza and a digital movie download, the line has blurred between e-commerce, groceries, and foodservice.

The result: Restaurants have free reign to get creative to stand out from the pack.

“It will be survival of the fittest for [the restaurant industry,” Stibel said. “Why not declare restaurant month instead of restaurant week when you reopen? Why not lean into subscription-based pricing or family meal deals?”

Consumers appear to be open to such broader offerings. According to Chicago-based research firm Datassential, 78% of consumers are interested in family meal deals like a buy-one take-one entrée deal. Additionally, 70% of consumers across all demographics are interested in restaurants as popup grocery stores selling bread/bakery items, fresh produce, and fresh meat/seafood.

Consumers appear to be open to such broader offerings. According to Chicago-based research firm Datassential, 78% of consumers are interested in family meal deals like a buy-one take-one entrée deal. Additionally, 70% of consumers across all demographics are interested in restaurants as popup grocery stores selling bread/bakery items, fresh produce, and fresh meat/seafood.

“We can be a one-stop-shop and have variety for the whole family,” Kim McBee, senior vice president of take-and-bake pizza chain Papa Murphy’s said, noting that their Vancouver, Wash.-based chain with more than 1,500 locations is uniquely positioned to appeal to the food safety-conscious crowd, as customers make the pizza themselves. “You have a lot of different people who can eat from one family meal kit, maybe mom wants this, or the kids want that.”

Of course, creative offerings will likely be inclined towards deals like coupons, special promotions, and free delivery, as millions of unemployed Americans struggle to get back up on their feet following a nationwide shutdown.

Rewarding brands with social conscience

Restaurant executives says consumers are rewarding restaurants that care about their employees and their communities, a sentiment they expect to continue long term. From being transparent about the treatment of their employees during a crisis to donating to people in need, customers won’t forget operators that prioritized transparency of policy and social consciousness during a time of crisis, they say.

“I think consumers will remember how you treated them and your employees during this crisis, and they will remember long after it’s over,” Eric Wyatt, CEO of Boston Market said.

Wyatt said that for example, managers used to get a free meal per shift while store-level employees would receive a 50% discount. During this coronavirus crisis, they quickly revised the policy to include free shift meals for all store-level employees.

“We’re learning along the way; it’s like building the plane while you’re flying it,” he said. “We want to make sure they appreciate that we’re trying to fulfill their needs,” he said.

“We’re learning along the way; it’s like building the plane while you’re flying it,” he said. “We want to make sure they appreciate that we’re trying to fulfill their needs,” he said.

Christine Specht, CEO of Wisconsin-based, 99-unit Cousins’ Subs sandwich chain agreed. She said that it all comes back to a brand’s attitude toward their customers and how they share that they care about their local communities. For example, during the coronavirus crisis, the company has launched the Cousins Cares campaign, which allows guests to pay it forward and reward essential employees in Wisconsin.

“I think there’s a continuing emphasis on what the social edict is,” Specht said.

Right now, for example only manager-level store employees receive paid time off, but she said that they might reevaluate these policies for a post-COVID world.

“Guests want to know who the people are behind the brand, how they’re behaving and how they treat their employees. […] guests will continue to choose brands that maintain a social conscience.”

Contact Joanna at [email protected]

Find her on Twitter: @JoannaFantozzi