When the news first hit in mid-August that eggs were being recalled because of possible salmonella contamination, Peggy Bevan of The Egg Shell restaurant near Denver decided not to take any chances. Not sure whether the eggs she had in stock were affected, she threw them all out — 90 dozen, along with the pancake batter and other mixes that had already been prepared using eggs.

“We remade everything,” Bevan said, after her distributor brought a new load of eggs an hour before opening the next day. “I’m just proactive. I don’t want to lose the reputation of my restaurant.”

Bevan said it turned out her eggs, which come from a local suppler, were not recalled. But the issue is still top of mind.

“Our guests ask us about it almost daily,” she said. “Everybody’s talking about it.”

The massive recall of more than a half billion eggs possibly tainted with salmonella has restaurateurs like Bevan taking a hard look at their suppliers and rethinking egg-handling practices as guests become more concerned about ordering eggs sunny-side up, Caesar salads or meringue-topped pies.

More than 1,300 people across the country at press time had been identified as having the strain of Salmonella enteritidis linked with the eggs, and health officials were expecting that number to grow.

Though the outbreak appears to be limited to two farms, the incident renewed focus on proposed reform before the Senate. That food safety bill would give the U.S. Food and Drug Administration added authority to recall foods that may be tainted and also would impose stricter rules concerning inspections and traceability. While the House approved its own food safety measure last July, the Senate has yet to act on its version.

The outbreak also raises ongoing questions about the mass production and distribution of products like eggs, which in this case were sent across the country to restaurants, grocery stores and foodservice facilities in 17 states.

Egg on many faces

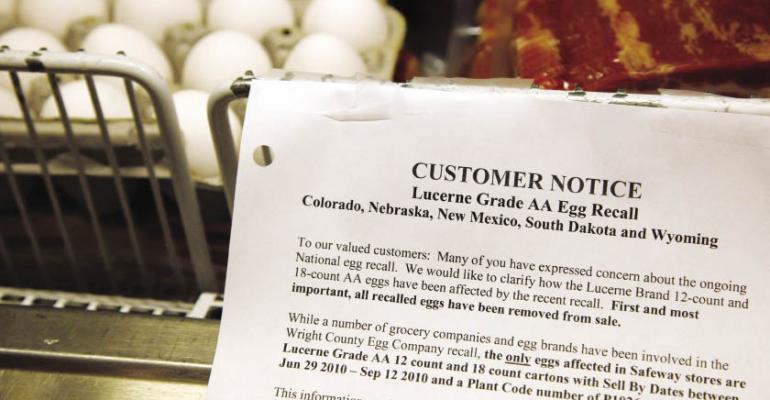

So far, the two Iowa farms involved in the recall were both reportedly linked to businessman Austin “Jack” DeCoster, who had been cited for various health, safety and employment violations in recent years. He owns Wright County Egg, whose eggs were specifically linked to the strain of salmonella that caused the recent outbreak. Another of his companies supplies chickens and feed to both Wright County and Hillandale Farms, which also recalled millions of eggs last month.

Many restaurants that found they had received tainted product said they handled the recall like any other — they pulled the product and found a safe alternative.

IHOP, based in Glendale, Calif., pulled eggs from some of its 1,466 locations. A few units had to go without shell eggs for a day or less, said Patrick Lenow, a company spokesman, but otherwise the impact was minimal for guests.

Many restaurateurs across the country said they feel safe because they buy eggs from a local farm, or those from organically raised or cage-free chickens — though the risk of salmonella contamination is not necessarily eliminated. Still, even those whose eggs were not recalled said they were forced to address the heightened awareness among their guests.

At Denver-based Snooze, an A.M. Eatery, a three-unit local breakfast-and-lunch concept, co-owner Jon Schlegel said his restaurants avoided the recalled eggs, in part because they rely on a local purveyor that has earned their trust for safety standards.

“We’re willing to pay more for that,” he said.

Schlegel said the restaurants go through about 15,000 eggs per week. Since the recall hit the news, he said, “we’ll get a few customers a day saying things like, ‘I’d like my eggs scrambled, no salmonella please.’”

To help address customers’ concerns, Snooze printed a flyer with information about the restaurants’ egg supplier, and employees were trained to answer guest inquiries about the recall.

In Colorado, Schlegel’s restaurants are not required to put a warning about eating undercooked meat or eggs on the menu, but, because of the recall, his restaurants may post such a warning in the future.

Columbus, Ohio-based Bob Evans Farms Inc., operator of the 569-unit Bob Evans Farms family-dining brand and 145-unit Mimi’s Café, also said its units had received none of the recalled eggs.

However, the company sent memos to all restaurants reinforcing proper food-safety guidelines and cooking techniques, said Margaret Standing, company spokeswoman.

How would you like that prepared?

Both Schlegel and Standing agreed though that guests should be allowed to order their eggs any way they want them.

Though the Centers for Disease Control recommends that restaurants use only pasteurized product when eggs might be served undercooked, most operators said that, whether one chooses to eat a rare steak or hollandaise sauce, it’s a matter of personal choice.

Still, the recall has sparked new interest in pasteurized eggs, said Greg West, president of National Pasteurized Eggs, based in Lansing, Ill. His company is the largest producer of pasteurized shell eggs, he said, including the Davidson’s Safest Choice brand available in retail stores and to foodservice accounts, as well as private-label brands for foodservice distributors.

San Diego-based Jack in the Box is among the national chains using pasteurized shell eggs in at least some of its units.

Since the recall, West said, business is up 65 percent, particularly from foodservice clients ranging from small independent operators to national quick- service chains. Demand has been highest from California, where retailers were quick to post signs about the recall in grocery stores.

West said his company’s eggs are pasteurized in the shell with a slow water bath that brings them to temperatures that kill the bacteria through the yolk without cooking the egg. The resulting product is safe enough to drink raw, West said, and functions just like an ordinary egg.

However, pasteurized shell eggs cost roughly 30 percent more, he noted.

For Kevin Bechtel, senior vice president of purchasing and menu development at Shari’s Restaurants, based in Beaverton, Ore., that 30-percent premium is “a tough nut to bite.”

Shari’s, known for traditional eggs Benedict and fluffy lemon meringue pie, uses a supplier in the Pacific Northwest whose eggs come from hens vaccinated against salmonella, he said.

According to The New York Times, the FDA considered mandating that hens be vaccinated against salmonella as part of the egg safety rule that went into effect in July. However, the agency said there wasn’t enough evidence to mandate vaccination, though about half of U.S. egg producers currently do it voluntarily.

The rule, which applies to egg producers with 50,000 or more laying hens, does, however, outline production procedures for shell eggs that are not pasteurized to prevent the spread of bacteria. It also requires that eggs be refrigerated during storage and transportation.

Bechtel knows the vaccine offers no guarantee. His focus has been on the operational aspects of salmonella risk, such as establishing procedures within Shari’s 104 locations to prevent cross-contamination and dealing with health department inspectors that want food handlers to use a fresh pair of gloves for the cracking of each egg — a challenge during a busy breakfast rush.

Walking on eggshells

For attorney Bill Marler, whose Seattle law firm specializes in foodborne illness, the issue should not be about “having restaurants and consumers handle eggs like they’re nuclear waste.”

The argument that the eggs would be fine if cooked enough is a knee-jerk reaction, he said.

“The CDC isn’t telling people to just cook the eggs,” he said, “they’re telling you to get rid of them.”

The problem is with the source, he added.

“What needs to be done is to get salmonella out of eggs,” Marler said.

At press time, Marler said he had about 40 clients looking to file lawsuits as a result of the salmonella outbreak.

Although the egg producers in this outbreak will likely be the primary target, restaurant operators also would be named in lawsuits — and putting warnings on menus about undercooked eggs offers little to no protection, he added.

The first suit Marler filed in this outbreak names the Baker Street restaurant in Kenosha, Wis., where a woman allegedly got sick after eating a Cobb salad.

Marler said it’s not clear whether the hard-cooked egg in the salad was the source, or possible cross-contamination. In that case, some of the restaurant employees were also sick with salmonella, he said.

Though the lawsuit also targets Wright County Egg, a source of the restaurant’s eggs, Marler said he’s hedging his bets in the event the egg producer files bankruptcy down the road.

“That would put the restaurants on the hook,” he said.

Contact Lisa Jennings at [email protected]