Operators looking to renegotiate their leases or move to more advantageous locations are in the driver’s seat as more restaurants and retail businesses become casualties of the unforgiving recession.

Landlords eager to keep their spaces filled are more amenable than ever to cutting deals, including reduced rents, generous build-out allowances and management agreements, especially for operators they view as having the cachet to attract customers, observers say.

“It’s good and bad in the sense that landlords are making concessions I haven’t seen them make before,” said Mark B. “Chipp” Sandground Jr., counsel for Kalbian Hagerty LLP, a Washington, D.C.-based law firm specializing in corporate and real-estate deals. “In a typical market, retail tenants don’t have a lot of traction when negotiating with landlords, but now what’s happening is tenants are vacating a lot of locations and they are looking for others to take over those spaces.”

Chip Roman, chef-owner of Blackfish, an upscale-casual concept with locations in Conshohocken, Pa., and Avalon and Stone Harbor, N.J., says he received a great deal from a New Jersey-based developer who plans to open a hotel on the Jersey Shore and needed a restaurant that would build a clientele while the facility was under construction and be an anchor for the project afterward.

“I was approached by a company, Shelterhaven Hospitality, who wanted to build a hotel on the bay,” he said. “They wanted me to set up a presence [in Stone Harbor], come in a couple years earlier, and get some buzz going for them. It was a very attractive deal. Essentially, the landlord built out the spot for me and we paid a percentage of the rent.”

Roman said the deal called for the landlord to pay up to $155 per square foot in build-out costs for the 175-seat restaurant, which totals 5,000 square feet in size.

According to Sandground, however, those types of build-out deals are being offered with less frequency and for less money than they were before the economic downturn.

“Everyone is insecure about their real-estate investments in a way they weren’t before,” he said. “The money out there for build-outs is shrinking. I’m not seeing consistency. In the D.C. market, for a high-end build-out, the norm probably was between $100 and $135 per square foot before the recession, but now I’m being offered as low as zero. Landlords would much rather give you rent concessions to get you in so they have a tenant occupying the ground floor of space and the building doesn’t look abandoned.”

Still, build-out deals are out there, he said, noting he is in the midst of brokering a few contracts that include generous build-out provisions.

“I have one client I’m representing who’s going to get $150 per square foot [in build-out financing],” he said, “and I’m doing a deal for one chef right now where the building is desperate for a restaurant [on the premises]. It’s a big association and they own the building. They’ve got 10,000 square feet in the basement and are willing to subsidize the deal at $150 a square foot.”

In New York, a notoriously difficult real-estate market to navigate, landlords are offering sweet deals to operators who are looking to open shop, something real-estate broker Frank Glasgall said he never thought he’d see.

“New York is unique in that the landlords are very tough,” he said. “But right now, with the market being very soft, they’re giving free rent. In some cases it’s one month a year for 10 years. Two years ago, you couldn’t get anything out of them, but you know, it fluctuates with the times.”

Glasgall pointed to chef-owner Charlie Palmer as receiving a great deal when moving his 20-year-old Aureole restaurant from its established Upper East Side location to a 10,000-square-foot space in the new Bank of America building in midtown Manhattan, which is owned by real-estate developer the Durst Organization. Various news accounts indicate that a generous new lease deal primed Palmer to move the restaurant to its new home. Palmer’s company would not elaborate on the specifics of the transaction.

“I’ve heard that Durst made a considerable investment, an inducement, in Charlie Palmer’s new restaurant,” Glasgall said. “I’m sure it was considerable, probably in the build-out, to get him in there.”

Chef-operators also are taking advantage of restaurant management deals, which can be extremely lucrative, particularly for well-known purveyors of established brand names.

Glasgall said the management deal is built on the premise that the hotel developer owns the restaurant, builds it out, and offers a percentage of sales and profits to the restaurateur.

“Generally, the chef-operator gets 5 percent of sales and 5 percent of profits,” he said, “but that can vary a percentage point or two.”

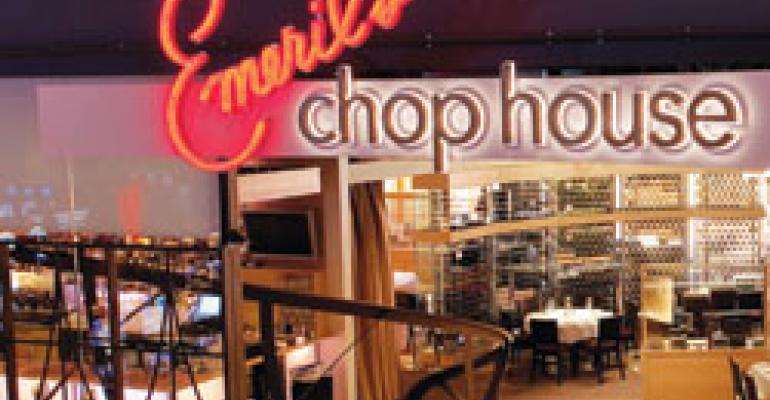

Celebrity chef Emeril Lagasse opened Emeril’s Chop House in May at the new Sands Casino in Bethlehem, Pa., as part of a management deal with Las Vegas Sands Corp., the Nevada-based developer of the Sands, Venetian and Palazzo hotel-casino properties. Dave McCelvey, vice president of operations for Lagasse’s Homebase restaurant company, said Lagasse receives a percentage of sales and profits from the 200-seat, 6,600-square-foot steakhouse, which anchors the Bethlehem casino resort. McCelvey would not reveal specifics of the deal.

“We started working on this deal several years ago,” McCelvey said, “and it was an opportunity to be one of the main food and beverage outlets in this new casino. Emeril carefully considered it, went to the casino and looked closely at the demographics of Bethlehem—it’s proximity to both New York City and Philadelphia—as well as the outlying suburbs, and decided it was a good idea. It’s a very fair deal that we have with them, one that puts us both in a good place to succeed. And so far things are going very well for us; we’ve been very well-received.”

Blackfish’s Roman said the hotel developer he signed on with has asked him to open another restaurant in the hotel once it is built. His participation in that restaurant will be based on a management deal.

“The guys putting the money out there right now are looking for some kind of return,” he said. “They are investing in people, not the building. They’re going after the ones who bring the dollars in.”— [email protected]