Nearly everyone consumes fast food.

Quick-service restaurant customers in the U.S. span all levels of wealth, income, age and region, according to a new study from Jay Zagorsky (left), an economist and research scientist at Ohio State University, and Patricia Smith, an economics professor at the University of Michigan.

And the researchers found that busy middle-class consumers exhibit one factor that makes them stand out among those who rely on fast food more than others: If they work more hours than typical, they are more likely than average to eat at quick-service restaurants.

These are the consumers who have a need for speed and depend on the “fast” in fast food, regardless of their socio-economic status.

“The guilty pleasure of enjoying a McDonald’s hamburger, Kentucky Fried Chicken popcorn nuggets or Taco Bell burrito is shared across the income spectrum, from rich to poor, with an overwhelming majority of every group reporting having indulged at least once over a nonconsecutive three-week period,” said the researchers in their study.

But the number of hours spent at work better indicates how frequently fast food is consumed, according to the study.

The Zagorsky-Smith study showed that consumers who routinely read ingredient labels were less likely to turn quick-service restaurants for their meals.

“Home food preparation is time intensive, but fast-food consumption is not,” Zagorsky and Smith found in their study, titled The Association Between Socioeconomic Status and Adult Fast-Food Consumption in the U.S. The study’s results were released in April in advance of official publication in November in the journal “Economics & Human Biology.”

“Fast food’s convenience is an important characteristic motivating its demand,” the researchers said. “Individuals with more leisure time are consequently more likely to prepare meals at home, while individuals who work longer hours are more likely to eat fast food.”

The study found fast-food consumers are more likely to live in central cities and the South, where fast-food outlets tend to be more densely located. They also are more likely to own a car.

“In addition, fast-food eaters typically have less leisure time because they are more likely to work and work more hours compared to non-fast-food eaters,” the researchers found. “Demographically, fast-food eaters are more likely to be male, younger, black and Hispanic.”

Identifying the fast-food consumer

Zagorsky said he and Smith launched their recent study after the Los Angeles City Council in 2008 banned freestanding fast-food restaurants in some poorer neighborhoods in South L.A.

“When I read the article about the L.A. ban, I was in the airport, eating a Wendy’s hamburger while I was waiting for my plane to be called,” Zagorsky recalled in an interview. “I looked around and said [to myself], these aren’t just poor people eating fast food in this airport; this is a cross-section of the United States.”

That, he said, got him wondering who actually eats fast food, based on survey data.

Zagorsky and Smith tapped into the National Longitudinal

Survey of Youth, based on research of 8,000 people in the U.S., to ask them how much fast food — such as McDonald’s, KFC, Taco Bell or Burger King — they ate over the course of the past seven days at three separate time periods: 2008, 2010 and 2012.

The researchers segmented respondents into 10 groups, or deciles, factoring in income, such as a regular weekly paycheck, and wealth, which includes household assets and investments.

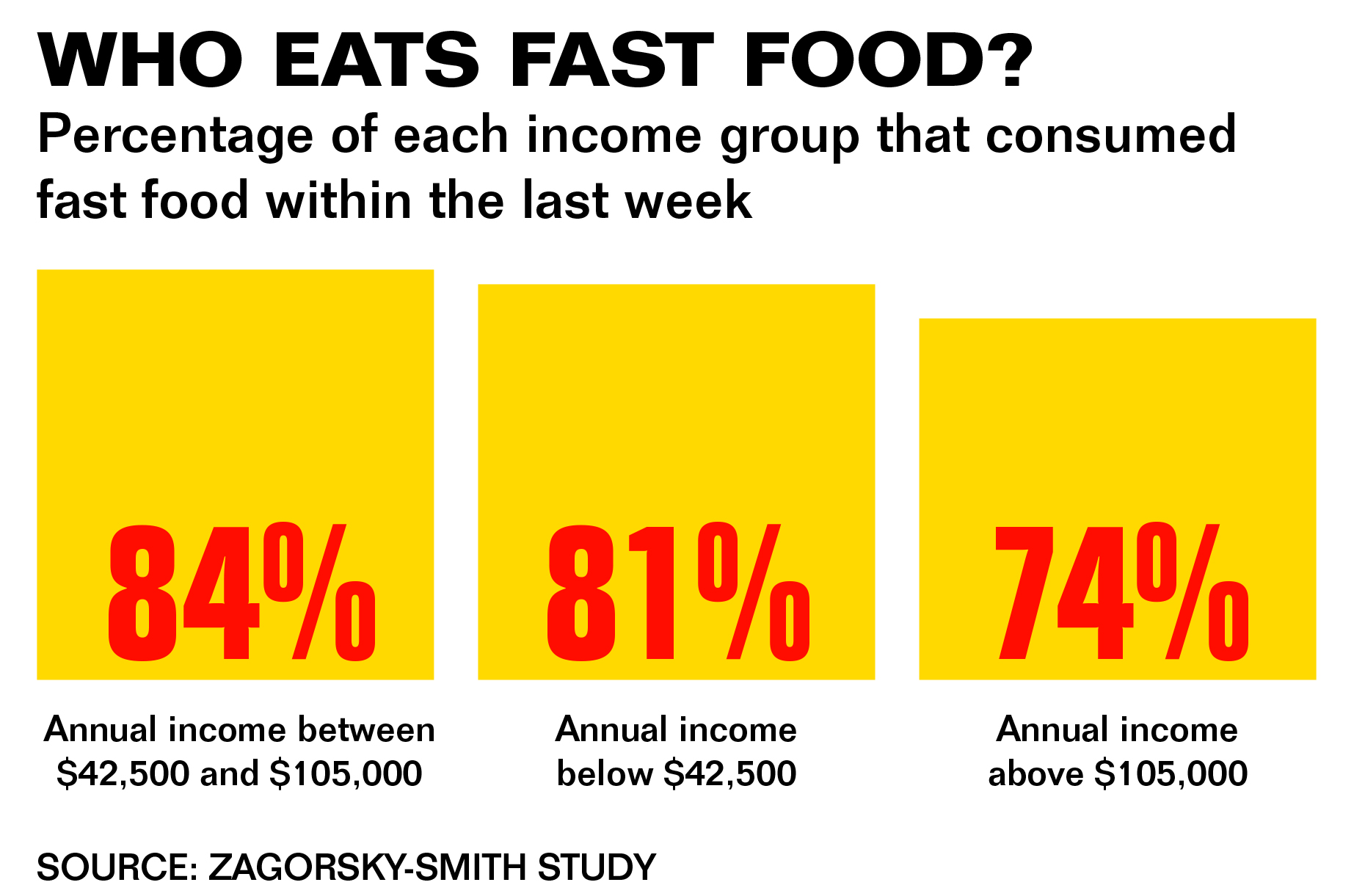

The study’s three lowest groups included individuals with annual incomes below $42,800; the middle four groups were those with incomes of $42,800 to $105,000; and the top three groups were individuals with incomes $105,000 and higher.

They found:

• 79 percent of respondents, across all income brackets, consumed fast food at least once in the given past week.

• 23 percent ate three or more fast food meals in that time period.

• 81 percent in the lowest income bracket ate fast food at least once during the study period, compared with 84 percent of people in the middle-income bracket and 74 percent in the highest.

“Realistically, you have nearly three-quarters of the richest people in the country eating fast food and about the same number of the poorest people,” Zagorsky said.

Anecdotal evidence supports that, he said.

“You see presidents like Donald Trump and Bill Clinton eating fast food,” Zagorsky said, “So you see both Democrats and Republicans, billionaires and poor people — pretty much everyone eats fast food.” President Trump has even tweeted out photos of his fast-food meals, such as KFC on his personal jet, and appeared in McDonald’s television commercials with the brand’s onetime mascot Grimace.

Though not everyone eats fast food, Zagorsky added, among those who do, the trend spans all economic classes.

The number of fast-food meals consumed in a week is somewhat similar across socio-economic classes as well, Zagorsky said. The survey found respondents in the lowest income bracket ate 3.6 fast-food meals on average over that period, compared with 4.2 in the middle group and 3.0 in the highest bracket.

“My father goes to McDonald’s once a week for coffee,” Zagorsky said. “So that counts as a visit as well.” Fast-food visits also include purchases of items like salads, he noted.

The survey analysis was paid for by the two researchers’ universities and based on National Longitudinal Survey data compiled by the U.S. Labor Department. Zagorsky said the Labor Department added nutritional questions to the NLS surveys to better understand the relationship between health and working.

“People who are not working very much tend not to go to fast-food restaurants,” Zagorsky said. “People who are working a lot of hours tend to eat a lot more fast-food meals. There is a relationship.”

The reason is clear, Zagorsky said. “If I’m busy, I don’t have time to cook. I’m still hungry. I still eat my three meals a day. If I’m walking by some place and they offer me something quickly, I’ll stop in.”

Quick-service restaurant brands have been responding to that market, with the world’s biggest burger brand, McDonald’s Corp., testing how to make the experience faster and more convenient.

Steve Easterbrook, president and CEO of Oak Brook, Ill.-based McDonald’s, said the company’s “Experience of the Future” initiative looks to tackle timing.

Easterbrook, in a January earnings call, said the company is looking to give consumers control of the experience and speed it up with self-order kiosks, drive-thru technology and smartphone order-pay applications.

The efforts address “a lot of the elements of the McDonald’s experience that can slow it down, not just for you, but maybe the customer behind you in the line are taken out of it,” Easterbrook said. “We believe we can have technology do a lot of that heavy lifting and any of the experience be better and the service will improve as a result.”

The burger brand is also addressing convenience with delivery tests.

Nutrition and age factors

Zagorsky and Smith studied obesity and its causes, and part of their research looked at how that affected fast-food consumption.

“We found that people that checked ingredient labels frequently really did have lower fast-food intake,” Zagorsky said. “That suggests that among people who care about diet and nutrition it will reduce their consumption of food at McDonald’s, Taco Bell, Burger King and Pizza Hut.”

“We found that people that checked ingredient labels frequently really did have lower fast-food intake,” Zagorsky said. “That suggests that among people who care about diet and nutrition it will reduce their consumption of food at McDonald’s, Taco Bell, Burger King and Pizza Hut.”

The researchers also found that those respondents who said they drank less soda also had lower fast-food intake, he said.

While the Zagorsky-Smith study looked at adults, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics in 2015 published a study that showed U.S. children and adolescents consumed 12.4 percent of their calories at fast-food locations.

“Kids ages 12 to 19 ate twice as many calories from fast-food restaurants as children ages 2 to 11,” the study found. “In total, close to 34 percent of children and adolescents from ages 2 to 19 ate fast food on a given day.”

A changing marketplace

Traditional quick-service restaurant brands have been seeing growing competition from supermarkets and newer health-oriented concepts, which may be changing the landscape for speedy, convenient prepared food.

But Zagorsky said the consumers’ workloads continued to be the biggest indicator of how likely they will be to patronize quick-service restaurant brands.

Consumers who put in an extra 100 hours of work each year were associated with about a half percentage point increase in fast-food consumption, Zagorsky said.

“From a business point of view,” he said, “this study indicates that the income demographics really aren’t that important. People across the income and wealth spectrum eat fast food. Staying away from really rich neighborhoods or really poor neighborhoods isn’t a good strategy, according to this particular research.”

The targeted neighborhoods for a strong fast-food business, he added, should probably be those where people work a lot.

“It’s time and convenience,” he said. “You aren’t looking so much for income, but people on time constraints.”

Contact Ron Ruggless at [email protected]

Follow him on Twitter: @ronruggless