Dick Elliott wasn’t a true restaurateur when he bought The Colony House in 1989. The recently retired corporate lawyer viewed the purchase as a real estate investment, a got-to-have property with an uninterrupted view of the historic harbor in Charleston, S.C. But it didn’t take long for the former lawyer to get hooked on the business, and within two years, he got the itch to create a new restaurant.

Elliott wanted “a neighborhood joint” designed for those who loved fine dining without its inherent pretense. His restaurant would offer a sophisticated Southern experience born of Low Country-inspired food and service centered on manners and gentility. In his place, ladies would always be served first, eldest to youngest, food would arrive from the left and empty plates would disappear from the right. He got chef Frank Lee and general manager David Marconi to join him, and they set about fleshing out the dream.

Trouble was, no one could think of a name for the restaurant, and though an advertising firm offered up dozens, the trio rejected them all. As the story goes, a frustrated Elliott told his partners, “We’re not getting out of this car until we name this damn restaurant.”

As they thought harder, they discussed the restaurant’s location, a block north of Broad Street, Charleston’s asphalt dividing line between its haves and have-nots. Though on the blue blood side of Broad, Elliott didn’t necessarily want it to be a fully blue-blooded place, just sort of one. And then it occurred to them: The restaurant sat slightly north of Broad.

“I said, ‘That’s it: Slightly North of Broad. I like it,’” Elliott recalls.

But Lee immediately truncated the name into an acronym, S.N.O.B., and objected. Elliott wouldn’t give in. He saw the moniker’s potential catchiness and stuck with it.

His hunch proved right. Not long after opening, a grandmotherly type pulled him aside and said, ‘“Mr. Elliott, do you know what people are calling your restaurant?”’ recalls Elliott, who knew what was coming next. “‘No, ma’am, what are they saying?’ ‘They’re calling it Snob.’ Well, I feigned horror and shock, and then I told her, ‘When you hear that, please tell them to call it Slightly North of Broad.’”

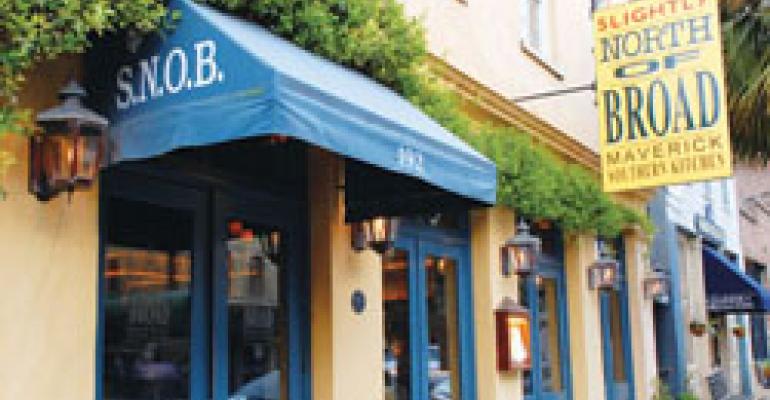

Rick Jerue, a regular customer and president of the Art Institute of Charleston, says most regulars call it “Snob,” too, but for brevity, not as a description. So do its owners: The restaurant’s front-door awning bears the acronym “S.N.O.B.” though its street-facing sign reads “Slightly North of Broad.”

“Locals call it Snob, but when you’re explaining it to an out-of-towner, they’re careful to call it Slightly North of Broad,” Jerue says. “Anyone who knows the restaurant knows that Snob doesn’t fit the experience.”

To this day, Elliott does not see himself as a gourmand, rather he calls himself “simply fascinated with the restaurant business.” As a corporate lawyer, Elliott traveled the country and was exposed to fine dining in many major cities. Though he loved the good food and wine, he was most intrigued with a restaurant’s operation. The notion that so many disparate activities could occur under one roof and work to one common end, customer satisfaction, piqued his curiosity.

“Of all the things I’ve done in my careers, I never stopped doing something because I didn’t like it,” says Elliott, who worked as a journalist before becoming a successful trial lawyer, followed by work as a corporate lawyer. “There was always something else dangled in front of me that was more attractive. That’s how I came to love restaurants.”

Elliott soon found out that admiring restaurants from afar and owning them were worlds apart. The Colony House was an established Charleston tradition with a staff in place and customers pouring through the doors. S.N.O.B. was started from scratch in a century-old building not designed for a restaurant. Lee says its outdated plumbing and lack of commercial venting were challenging in the beginning.

“It took a lot to get the place right, and we opened it up without a penny,” Lee says. “We were walking a tight rope when you think about it. It was…hard work that made that place a success.”

Having served in leadership roles for other businesses, Elliott refused to listen to others’ beliefs that a restaurant would be different. When a business cares first about its customers, teaches employees to do the same and sets clear management philosophies that all can follow, success is imminent, he says.

Elliott also credits the experience of Lee and Marconi with giving S.N.O.B. an immediate identity by setting high standards in both ends of the house.

“I wanted Slightly North of Broad to be a place to showcase Frank Lee’s talent,” Elliott says, adding that Lee and Marconi since have been given equity ownership in the company. “David understood that our service would come with a heavy dose of hospitality, which for me means acting like you’re glad your guests are there.”

A South Carolina native, Lee is widely recognized as one of Charleston’s premier chefs. His career began in 1973 as co-owner of a natural-foods restaurant, which he humorously describes as “a quintessential militant-vegetarian restaurant.” Seeking to refine his cooking, he left home to work for chef Jovan Trboyevic at Chicago’s Le Perroquet and chef Yannick Cam of Washington, D.C.’s Le Pavilion. He returned to South Carolina in the 1980s as chef at Wild Dunes before moving onto Restaurant Million.

While Lee loves classic French fare, his desire has been to apply its techniques to traditional South Carolina cooking.

“I worked at a lot of French restaurants where we did incredible food, so I wanted to bring that to the table here in the way that anybody could afford,” Lee says. “Here, you can get meat loaf with gravy made from reduced veal stock, or you can get a charcuterie platter with house-made sausage and rillettes. You can go so many different ways with our menu. You’re able to eat big, small, rich or light and always have it done in a consistent manner.”

Where possible, Lee draws on local purveyors for seasonal foods and tries “to stay in the rhythm” of nature’s schedule. He particularly likes whole animals whose non-prime parts typically become the base for sausages, terrines or one of several daily specials. The goal, he says, is to turn simple foods into great dishes.

“We do deep-fried chicken with local scratch-and-peck chickens, and then we enrich the gravy with Madeira and caramelized onions,” he says. “We have our core menu that locals have preferred during our 15-year history, but we add a lot of specials every day: two to four main courses, two to four appetizers and two to four desserts. That’s where we express our seasonality, creativity and locale.”

Lee, who is credited with helping launch the careers of other chefs, loves to instruct. Despite the need for systemization in a restaurant, Lee teaches his cooks to learn the trade using instinct along with formula.

“Technique is what you train, and when they get that, recipes become reminders,” Lee says.

Thus, he encourages his staff to develop the restaurant’s specials.

“We’re not teaching them how to make widgets or weld car seams, we’re teaching them to weave their spirits into foods that enrich people’s souls,” he says.

Karen Barker, chef and co-owner at Magnolia Grill in Durham, N.C., says Lee has made great strides to simplify grand foods without robbing them of their elegance.

WEBSITE:

“I like the fact that Frank is a classicist who utilizes all different types of ingredients, just about any cut [of meat] you can think of, to make real food,” Barker says.

She met Lee years ago when paired with him at a Charleston food-and-wine dinner featuring prominent local chefs.

“He’s not afraid of flavor,” she says, “and I think that keeps his food real. His food has lots of character, lots of very deep and soulful flavors.”

Despite S.N.O.B.’s nickname, Lee says his food purposely is not trendy.

“We’re not a sprinkles-on-the-plate place or a weirded-out food science place,” he says. “We’re just a place trying to make a good product every day with quality.”

Placed squarely in Charleston’s business district, S.N.O.B. has become the place for business power lunching, Art Institute’s Jerue says. But with 80 seats, demand is high, which forced S.N.O.B. to start taking reservations several years ago. While that slowed the frenetic pace some, the restaurant routinely does 250 covers at lunch.

“It’s almost like I’m going to a fast-food place but with quality food,” says Jerue, who lunches there at least twice a week and returns for dinner some three times a month.

Turning and burning tables while providing hospitable service is a tremendous challenge, says Peter Pierce, S.N.O.B.’s general manager. Teamwork is required to pull it off to make sure every guest, even those outside of a server’s station, is tended to.

“We call it sharking, where all the staff attacks a table,” Pierce says. “You never go to a table by yourself to clear it, you get two or three of your support staff. You have to move that fast to turn tables quickly.”

MENU SAMPLER Sesame crusted tuna medallions: house-made kimchee, nori rolls, miso, cucumber salad, pickled ginger and wasabi $14.95Prince Edward Island mussels: poached with white wine, garlic, parsley and a touch of butter $8.50 Grilled Southern medley: chicken breast, zucchini, eggplant, tomatoes, goat cheese croutons with pesto, Pecorino-Romano and balsamic vinaigrette $15.50Maverick shrimp and grits: local yellow grits, house-made sausage, country ham, tomatoes, green onions and spice $16.50 Maverick beef tenderloin: grilled, deviled crab cake, béarnaise and green-peppercorn sauce $27.50 Chocolate trio: chocolate pudding cake, coffee liqueur, pots de crème, chocolate ice cream $7 Sour cream apple pie $6

That S.N.O.B. hosts a see-and-be-seen lunch helps the restaurant and the staff in two ways, Pierce says: It’s always busy, and it’s easier to remember customers’ specific preferences.

“When Mr. Conner comes in, we know to put a sweet tea on the table,” he says.

To help remember those touches, the staff uses OpenTable software to store specific data.

“It’s so cool to get a guest who asks, ‘How did you know I like that?’” Pierce says.

The pace slows some at dinner, which Pierce says draws more Charleston visitors than locals. While the staff aims for hospitality, he says serving tourists gives them the chance to pour on dignified but reserved Southern charm.

“We don’t want them too casual, but we also don’t want them robotic,” he says. “It’s always ‘Yes, sir,’ and ‘Yes, ma’am,’ always proper. We never want them to get too comfortable, touching tables or chairs. We want them to be professional. Guests go to plenty of places where they won’t get that.”

Jerue says when he walks through the door at S.N.O.B., he feels like he’s home and that he’s someone special. He believes that’s a reflection of Elliott’s and Marconi’s nonstop training and insistence that the dining experience is warm and welcoming.

“I know the people who own the restaurant are watching it all the time and making sure it lives up to their expectations,” Jerue says. “And I can tell you, theirs are extremely high.”