An amendment to a federal law intended to prevent identity theft by requiring retailers to mask credit card numbers and expiration dates on sales receipts has spurred a rash of lawsuits against several prominent restaurant companies.

In-N-Out Burger, the Walt Disney Co., El Pollo Loco, California Pizza Kitchen, Levy Restaurants, The Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf and other foodservice operators are defendants in the lawsuits along with more than 40 well-known retailers, including Rite-Aid, AMC Theaters, Block-buster and the Bristol Farms food store. The companies are accused of printing credit or debit card numbers and expiration dates on their customers’ sales receipts and face potential damages in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

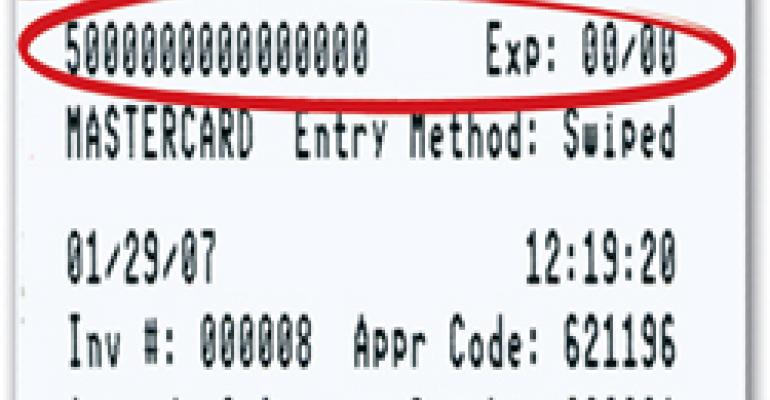

All of the companies are charged with “willful noncompliance” in violating a statute that requires retailers to truncate credit card numbers and expiration dates by printing no more than five digits of the card’s account number on sales receipts. The statute went into effect Dec. 4, 2006, as an amendment to the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act, better known as FACTA, which President Bush signed into law in 2003 with the intention of improving accuracy in the reporting of consumer credit histories.

Some of the lawsuits were filed Dec. 5, 2006, the day after the rule took effect. Plaintiffs’ attorneys initially sought class-action status in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles and Orange County, Calif., because of a favorable federal appellate ruling in that state defining merchants’ “willful” misconduct. But lawyers representing the restaurant companies named as defendants in the lawsuits fear that similar complaints will be brought against foodservice operators nationwide in the months ahead.

Attorney Robert Wallan, whose Los Angeles-based law firm Pillsbury, Winthrop, Shaw, Pittman LLP is representing several of the defendant companies, called the lawsuits against his clients a “frivolous shakedown.”

Although no defendants have yet filed responses, Wallan expressed optimism that the courts would deny class status and ultimately dismiss the cases altogether.

He explained that his confidence is fueled by the fact that the plaintiffs’ attorneys cannot identify a single person who was harmed by the information found on the receipts, which generally included expiration dates, not the sort of personal details that leave people vulnerable to identity theft.

Even more significant, Wallan said, is that in the majority of the cases the customers asked for the entire receipt before they left the retail or restaurant establishment.

“Companies have to comply with statutes, no doubt,” Wallan said. “But we are considering these cases frivolous. They don’t have a single person that was hurt or damaged, and yet they are seeking monetary damages that could reach into the hundreds of millions of dollars. It’s your classic shakedown. It’s just ridiculous.

“If you don’t have actual damages, you don’t have any damages. So there are no damages to recover.”

Wallan said the damage claims in the lawsuits are based on penalties in the law calling for $100 to $1,000 fines per alleged violation. If those dollar figures are multiplied by the number of receipts and the number of units in the targeted chains, the result could be in the billion-dollar range.

The amount of damages could potentially exceed the total market capitalizations of some of the defendant companies, Wallan charged.

“The damages they seek would be so enormous that it would be unconstitutional,” he said. “You can’t have a $50 million fine for forgetting to put a quarter in the meter.”

But he added that he doubted any court would assess the fines, given that the statute specified “willful” misconduct and none of the defendants deliberately attempted to harm their guests.

Moreover, he said there is confusion in the law over exactly what the penalties would be penalizing, given that the statute was added to a law intended to promote more accurate credit reporting.

But Mark Moore and Greg Karaski—the plaintiff attorneys from Spiro Moss and Barness in Los Angeles—dismissed Wallan’s defenses as baseless and immaterial given the letter of the law.

They said it doesn’t matter that none of their clients was hurt by the retailers’ noncompliance, and they stressed that it is too early to say that no clients would be hurt in the near future.

They charged that retailers knew three years ago when President Bush signed FACTA into law that they would have to upgrade their point-of-sale systems to obliterate credit and debit card numbers.

Moore said it did not matter that many of the defendants operate hundreds of outlets in many locales with different hardware.

“The day after some of these companies were served, they upgraded their software,” Moore said, quickly noting that the companies that made the change remain defendants in the lawsuit. “So if they could do it in a day, why couldn’t they have done it in three years?”

Karaski defended the decision to file the lawsuits soon after the rule to mask credit and debit card numbers on receipts took effect.

“Everything we’ve done is consistent with the rule of professional legal conduct in California,” he said. “The law gave them a long window, and every day that goes by more of these receipts are printed and pose a risk to them and a risk to consumers.

“What were we supposed to do? Wait another six months or something? Wait until summer for an accrual of all of this? They’d be in even deeper trouble than they are now. That might explain why so many of them so quickly brought themselves into compliance.”

But Moore stressed: “Just because these guys are now complying, that does not get them off the hook. They had three years to do this, and they are still defendants.”

Pressed to explain how they found so many clients so quickly, Moore called the question “inappropriate,” but added, “A lot of them had been victims of identity theft in the past and didn’t want it to happen to others.”

A third Los Angeles-based lawyer at another firm for the plaintiffs, Douglas Linde, would say only that he “had not filed against any restaurants” and that he would not discuss his strategy. But he refused to return a follow-up call for clarification after it was determined that he is indeed suing In-N-Out Burger.

Spokespeople for El Pollo Loco and Levy Restaurants said they do not discuss pending litigation. Calls to In-N-Out Burger were not returned.

Wallan, the defendants’ attorney, said what bothers him the most about the cases thus far is that few news outlets report that no private credit card information was ever disseminated publicly.

“These people got their receipts back,” he said. “The printed receipt got to the plaintiff. No secret information was disclosed. Printing an expiration date only on a sales receipt is not a willful act of identity theft. Therefore, there is no harm.”

While Wallan admits that his clients had a window of time to make what he termed a “simple software upgrade,” security experts argue that updating a large chain’s POS system is far more difficult than it sounds.

Mike Petitti, an expert in POS technology for Chicago-based Ambiron TrustWave, a leading provider of data security services and software, stressed that he was not taking sides in the litigation. He mildly criticized the plaintiffs for their impatience and he mildly criticized the defendant restaurant companies for failing to embrace truncation software tools that the major credit card companies had long been promoting among merchant-clients.

Petitti said that among retailers that accept credit cards, most have followed an industry standard known as Payment Applications Best Practices, software applications that reside in the POS software and can easily edit or delete sensitive data from printed materials in order to protect consumers’ identities.

“Retailers want to make sure that they have domain in their environment,” Petitti said. “And when it comes to their POS systems, which can be scattered over thousand of miles, thousands of outlets in different states, the ideal is to run the same version of the same software at the same time.

“But that is easier said than done, and without stopping business operations to make the upgrade, it is a challenge.”

A spokesman for a major sandwich chain uninvolved in the rash of lawsuits spoke firsthand to the challenges Petitti said big chains face. A franchised outlet of the sandwich chain in Manhattan gave a credit card receipt to a Nation’s Restaurant News reporter with the entire credit card number and expiration date on the receipt.

“Most likely, your colleague’s experience was an isolated incident,” the spokesman said. “I checked with our retail technology people who told me that our approved credit card processors that supply the hardware and software to our franchisees are in compliance with this law.

“However, since all our locations are franchised, we can only advise them about the regulations, the benefits of going through the approved sources and suggest that they do so.”

Meanwhile, Tena Fiery, a spokeswoman for the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse—a San Diego-based advocacy group that pioneered and campaigned for stronger identity theft legislation back in the 1990s and takes credit for the strengthening of FACTA—said that while her organization condemns the spate of lawsuits, she supports the enforcement of the amendment.

“This is a noble purpose to keep credit card numbers off of the receipts,” she said. “The idea of limiting identity fraud by keeping personal information out of the public domain is crucial, and concealing credit card numbers is just another way to do that.

“But I must admit. I don’t understand these lawsuits. I guess it’s true. Anybody can sue anyone for anything.”